Enchantment has called me since I was ten years old. It called me to find the spark behind the mask of things, and to doubt the ordinary. In those days I indiscriminately called it Magic, though just as often called it Imagination. Imagination was magic, but not Imagination in the way adults talked about it, nor magic in the way it was usually portrayed (adults didn’t really talk about magic). It would be many years, many books, many mistakes before I grew to articulate the difference for myself. Tolkien’s “On Faerie Stories”1 was an immense help, and I might be best following Tolkien in calling it Faerie. Magic, Imagination, Enchantment; whatever we call it, it seems to be returning to those parts of the world that have tried to drive it out. We are in the midst of a magical revival in the West – the publication of Grimiores, astrological texts, and the explosion of Tarot readers, and magical counseling and other services. Chaos magic has shown up on emerging trends lists, and there is a hefty infusion into pop culture that I wont rehash here. I am fairly happy about all of this, though I also think that much of it is beside the point of my particular calling.

The growing prevalence of Tarot, astrology, journeying, and the rest are re-introductions of what I think of as “enchanted” practices to the western cultural milieu. I think this is good, it helps to re-enchant many lives by reintroducing things that the regime of disenchantment has cast out. However, I think it is a mistake to think of those practices as inherently magical, and other practices as inherently disenchanted. In this time and place, reading Tarot is seen as a magical practice, and reading a novel is not, but that is a matter of history, not metaphysics. My calling in the realm of faerie is to break down the way we distinguish between the enchanted and the disenchanted; or rather, relocate it. Practices are not themselves enchanted or disenchanted. Enchantment is a relationship, an openness to the awe and wonder of the universe. It is a sensitivity to the numinous. Historically, certain practices were identified with the world of enchantment or magic by those that were trying to do away with it. They were singled out because they pointed beyond the worldview that was being constructed, first by religion (mostly Christianity), and then later by science.

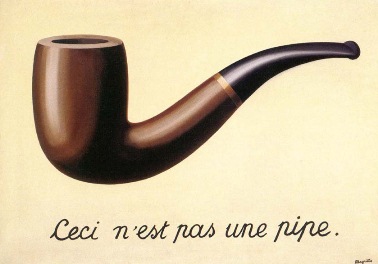

These enchanted practices broke the rules of the mainline religious and scientific worldviews – In popular religions, they defied God’s will (by being attempts to anticipate or control the future), and later, in science, by defying the rational “clockwork” universe and introducing ghosts into the machine. They became scapegoats2 in the biblical sense, where the “sins” of the enchanted universe were attached to these practices, and they were sent out to the wilderness to die, as a way of ritually slaughtering that relationship to the universe and sealing off the gates to faerie. By driving out (or really, driving underground) certain practices, like fortune telling, and astrology, and many others, the metaphysics of enchantment attached to those practices was culturally repudiated throughout Europe, and in many of the places colonized by Europeans. Of course, those practices never really left us, they were driven underground in some quarters, made illegal or quasi-illegal, or at the very least pushed past the bounds of respectability. They have of late had a re-infusion of vitality. But I do not think the work of re-enchantment ends with their triumphant return, because they were never the source of enchantment themselves. “Enchanted” practices can also be dis-enchanted, as is evidenced by purely therapeutic approaches to Tarot, which take the Tarot cards as “nothing more” that a canvas onto which one may project the contents of the unconscious.

If enchantment, or faerie, or magic are not the sole province of practices like tarot, astrology, and ceremony, then what is really going on with enchantment and disenchantment? How can anything become disenchanted? If enchantment is a relationship, how can we be put out of that relationship, or blocked from forming it? This is a complicated question because I think there are many forces at play on this battlefield. The one I focus on has to do with meanings in both senses of the word; both the linguistic one, where “meaning” is almost interchangeable with “definition,” and the existential one, where meaning is almost interchangeable with “highest purpose, or reason for existing” (or perhaps, for philosophers out there, telos.) On this front of the battlefield, re-enchantment is not about putting “something more” into our understanding of Tarot, an additional causal force rearranging the cards. Rather it questions the idea of “nothing more that projection of the unconscious” and especially the “nothing more” part of that clause, a dismissive spin on the meaning of a Tarot reading, and more importantly a dismissive spin on the contents of the unconscious. Much of the work of disenchantment has occurred in the realm of meaning, through battles great and small fought in the way we think and talk about things, on the semantic layer of our world.

The Semantic Layer

I often interact with the world on and through the semantic layer, and I am probably not alone in this. The semantic layer of the world is the aspect of the world that is what things mean, or what things are “about” (this is known as intentionality, and is related to what Teilhard de Chardin called the Noosphere). It can be difficult to understand this, because for many of us, it is inseparable from our everyday experience of the world. As an example, I see before me a coffee cup. Part of what that cup is, part of what makes it a cup, is that I see it as such – I think the word “cup” when I try to name it, and I see its form as related to a particular function – getting coffee into my mouth. But if you imagine an intelligent species from another planet visiting earth and encountering this cup for the very first time, they would see the shape of it, the color, and so on, but would not necessarily have the idea of cup-ness in their minds. They might not know what the object was for, and because of that, would not really have access to what it means. This world is often accessed and manipulated through language, and for those of us fluent in (any) language, the semantic layer of reality is omnipresent, especially in familiar environments where we know what things “are.” We don’t have to experiment with the cup to figure out what it is, what it means to us, or what it is for. The meaning is given. The semantic layer is where the ideas, concepts, and meanings for everything we encounter lives, and it is usually invisible to us, because (to borrow a turn of phrase from Lee Shulman3) the semantic layer is not something we look at, it is something we look with.

The given-ness of meaning in the semantic layer is often helpful. It would be very difficult to live in the world if we had to constantly figure out what things were, and what they were for. So we have a layer of learned and discovered meanings for things, generated in concert with others, often relating to the development and refinement of our ability to use language, and this semantic layer is often the means through which we both see and interact with the world. This makes the semantic layer an incredible source of power – to be able to name things, to give them their functions, and their meaning is to do nothing less than to condition what people see as possible, and to be able to pattern what gets recognized as real. This power has made the semantic layer a battlefield of warring interests for a very long time. I gave a talk about this in my Masonic lodge a few months ago, in a talk about Rhetoric as an esoteric art that I won’t repeat here, though the main point of it is that Rhetoric, in its ancient and contemporary forms, is the art of manipulating and reshaping the semantic layer, and there is a continuity rather than a difference in kind between everyday experiences of things like advertising, and the power to shape the world.

We talk this semantic world into existence, and arrange our lives according to its horizons. This is related to what Tolkien called “subcreation,” though he only suggests this goes on inside the work of the artist or writer. We live in stories, and they are often not stories we have had much part in framing. Disenchantment is itself a spell, the weaving of a story-world in which our own sense of meaning and our own stories are cosmically unimportant. It is quite a tale, which, if internalized, just might convince people to abandon their own sense of meaning, their own horizons, or at least treat them as modest and secondary epiphenomenon to the “real” story of cosmic meaninglessness. At best, our stories get relativized to the story of mechanism and emptiness, which serves as the backdrop against which we play for a time. It is a story which perfectly functions to undermine our own connection to life and to poison the deep urge of our own purposes. In the disenchantment story, we pull back or cede altogether our roles as subcreators. It well serves empire, and all its screeching progeny of colonialism, sexism, racism, and the rest. Resistance is futile.

This is big magic, hidden under a spell which names the stories we tell and the meanings we make perhaps privately meaningful, but cosmically irrelevant. The story of disenchantment gets to hide itself as the default, as empire and the children of empire ever do, even though it too is a story, with no more right to us than any other story. Like any story, it stands in relation to actual creation; the living and breathing cosmos, reality itself. This reality beyond our stories is the Noumena, in Kant’s original sense of the word; the world beyond the stories we tell and the patterns we create. For Kant, the Noumena was the “thing in itself” which we could have no direct knowledge of, because we were unable have experiences without a lens, a filter that orders and arranges the offerings of deep reality into something that we can make sense of. For Kant, our consciousness arranges reality into space and time, among many other things. The Noumenal, “reality in itself” was beyond our capacity to even begin to imagine.4 I think that the semantic layer is an aspect of that relationship to the real – we see the world with it, and may not be able to see without it. The Noumena, filtered through our lenses, gives us the Phenomena – the world as we experience it. Intentionality – the meaning and idea of the things of the world (the “cup-ness” of the cup) is a part of the phenomenal world, though not quite as close to the foundations as space and time. If we think of our meanings and stories as part of the sense-making faculty that Kant saw as co-creating the Phenomenal world5, then stories are a part of how we (or others) co-create the worlds we experience. Big magic.

Big Magic

We live inside stories, or narratives, or world-views, and all of these things are subcreated things that allow (or prohibit) us from connecting to the world and each other in different ways. They condition our interaction with the vastness of the real. When our stories are in right-relationship with reality – as interfaces to the real – they connect us to Noumenal creation, the living breathing cosmos that we live inside. But the story of disenchantment and empire has stood in the place of creation. It takes itself to be Reality, instead of an interface, or represents itself as such. It is the demiurge, it is Saklas; the created that mistakes itself for the creator. It stands in for our relationship to the real, and our relationship with it becomes a kind of unintentional idolotry. This isn’t an intrinsic feature of the currently prevailing worldview, however. I suspect that disenchantment started out as escape from the tyranny of superstition used in much the same way; to control, to limit, to inspire fear. The confusion of map and reality is a problem that recurs: in classrooms, where theories in physics meant to describe the world become mere procedures to memorize and repeat, or when a philosophical text becomes the object of study, rather than using it to see the world anew, in art it is gimmick artwork about itself, rather than artwork that calls our attention outward or inward into relation with something deeply real. In the process of standing-between, these things, which should be ways of relating to the real, instead themselves become the object we relate to, placing us in a second-order (or third, or fourth, or…) relationship with the world. I’ll also add as a note – we can fall out of relationship with the real just as easily with our own ideas and understandings as those we receive from others. This is a potentially a big discussion on its own, though, perhaps for another time.

Our acts of subcreation occur in a relationship to the real, but as subcreations, are conditioned by our own limitations as human beings. Our artworks and understandings can themselves also become legitimate objects of attention without standing-in for the real. They are, after all, also things in the world. The problem occurs when they usurp the relationship with the real and become the condition and whole horizon of our relationship to the real; then we have the demiurgic situation. The smallness of what we have created becomes its defining feature, and the ways it does not connect instead become limits for us. It is like the difference Tolkien describes between allegory and appliciability. In allegory, the relationship to the universe is fully figured out by the smallness of one rational mind, which makes explicit and direct connections by limiting other ones, and the author determines the connections. In applicability, connections are made by the reader, the author just tries to build a landscape fertile for connecting to the real. Demiurgic relationships close off our relationship to the real, while genuine connections open us to connect to the real. Both are related to the same aspect of our sense-making – its limitations. Genuine connection happens when we sense and accept those limitations and look beyond them, at what they would be pointing at. Demiurgic connections accept those limitations as the limits of our own horizon. Disenchantment is the systematic limitation of experience to the allowances of a worldview that is rationalistic, physicalist, and meaningless.

Praxis

I think that the construction, manipulation of, and hijacking of worldviews and stories is the site of tremendous conflict, and untold resources have been invested in it (for starters, count all advertising, and really, most media as resources invested into this battle.) Praxis, then, is the work of trying to get oneself into closer relationship with the real – to have a story and a world-view that enables your connection to the real. I think this is a matter of having a good story/worldview, and persisting in using the story to look beyond what it says, into the world that the story is speaking about, an ongoing commitment to the insufficiency of the story to reality (a kind of via negativa)

One specific exercise I do works as a practice of breaking out of conventional meaning, and to look at the world, and the things in it, with fresh eyes. It is simple to describe, more difficult to actually do – and is a kind of mindfulness, where you observe while trying to suppress the name/understanding that arises in conjunction with that observation. I find this an especially striking exercise in cities, which have a very thick semantic layer, laden with well-worn meanings, and reaction to those meanings. The honking of horns is an irritation, and means anger and frustration. Skyscrapers are buildings, full of offices and people and business dealings, and so on. But to experience the honking horns and their echo off the concrete canyons formed by skyscrapers, that is a different way of being in the city. The “interface” is not gone, because our senses are still an interface with the real. However, the semantic layer is quieted, and different ways of relating to the city become available through the channels of the senses, and we can play with new stories, new understandings, and see how those might enable different kinds of interactions with the city. But this is just an example of the long and difficult work of trying to relate authentically with the real. It is a work that you can attempt through much of the work of human effort, in the humanities, arts, and the sciences., and those same works of human effort can lead you far astray, and set themselves up as idols.

Our stories and our worldviews are the ways in which we interact with deep reality, and they are a thing we get to construct, or, ideally co-construct with reality itself. They are relational, in which we both push and are pushed, and that interplay can be a struggle or it can be a dance. This is the big magic in which we are all embedded. This magic can go wrong, however – we can lose ourselves in our spells, turning them from tunnels into the real into lacunae, as the current “disenchanted” worldview has done. The work of re-enchantment is to re-establish a genuine connection to the real, not by perfecting our worldviews, but by falling out of the pattern of making them into idols.

Footnotes

- Tolkien, J.R.R. On Faerie Stories

- Leviticus 16:10

- Shulman, Lee.

- Kant, Immanuel. “A Critique of Pure Reason”

- To be clear, Kant didn’t think this – he thought that it was the structure of Reason that patterned the Noumenal “real” into the Phenomenal world of experience. But I think his method applies to help understand the Semantic layer, which again, may be a difference of degree than kind.

You must be logged in to post a comment.